Around 355 B.C., Plato, the great Greek philosopher, wrote a book called: “Timaeus”. In this book Plato, then in his seventies, chose the literary device of writing as though he was a young pupil listening to his teacher Socrates discussing various philosophical matters with a group of friends. The main reason why this book is famous is that, in it, Plato has recounted the story of a mysterious continent called Atlantis. In the book, the story is attributed to one of the friends present, Critias, who says it is “derived from ancient tradition”.

“Once upon a time,” according to the account given in Plato’s book, “there was, beyond the strait you call ‘The Pillars of Hercules’, an island larger than Asia Minor and Libya together…On this island of Atlantis, ther e existed a great and admirable kingdom.” Plato proceeded to describe Atlantis further in another book: “Critias”, also written around 355 B.C. Atlantis was a semi-tropical island continent of, perhaps, 400,000 sq. kms, with an estimated population of 20 million. For centuries (12,000 to 9,000 B.C.), said Plato, the Atlanteans were the dominant civilization in their half of the world, ruling a Mediterranean empire that extended to the borders of Egypt and Italy. Eventually, wrote Plato, they became “obsessed with the wrongful pursuit of material gain and power”, and tried to conquer the entire Mediterranean world. They were beaten back by the ancestors of the Greeks.

e existed a great and admirable kingdom.” Plato proceeded to describe Atlantis further in another book: “Critias”, also written around 355 B.C. Atlantis was a semi-tropical island continent of, perhaps, 400,000 sq. kms, with an estimated population of 20 million. For centuries (12,000 to 9,000 B.C.), said Plato, the Atlanteans were the dominant civilization in their half of the world, ruling a Mediterranean empire that extended to the borders of Egypt and Italy. Eventually, wrote Plato, they became “obsessed with the wrongful pursuit of material gain and power”, and tried to conquer the entire Mediterranean world. They were beaten back by the ancestors of the Greeks.

Then, according to Plato, “in a single dreadful day and a single dreadful night,” Atlantis was swallowed up by the sea.

Aristotle, Plato’s most famous disciple, believed that Plato had made Atlantis up, and this doubt has continued over the centuries. L. Sprague de Camp, in his scholarly work: “Lost Continents”, has analysed the evidence carefully and convinced himself that “the most reasonable way to regard Plato’s story, then, is an impressive, if abortive, attempt at a political, historical and scientific romance – a pioneer science-fiction story”; his view is that, like Thomas More’s “Utopia”, Plato’s story described an ideal community as preconceived by the author.

evidence carefully and convinced himself that “the most reasonable way to regard Plato’s story, then, is an impressive, if abortive, attempt at a political, historical and scientific romance – a pioneer science-fiction story”; his view is that, like Thomas More’s “Utopia”, Plato’s story described an ideal community as preconceived by the author.

However, more than 2,000 books on the subject disagree, and while it may be comfortable to take the orthodox line, the chances are that Atlantis actually existed.

For Plato goes out of his way to report exactly what were the origins of the Atlantis tale: Solon, a famous Greek elder statesman, had been given the story by the Egyptian priests of Sais, and had planned to write a poem on the subject. (Historically, there is no doubt that, after Solon’s retirement from public life, he travelled to the Mediterranean as a businessman, and there are a number of contemporary witnesses of his visit to Egypt around 600 B.C.) He told what he knew to an equally renowned Greek, Critias, whose grandson was the friend of Socrates who narrated the story in Plato’s books. These were all highly eminent people. Also, Plato affirmed flatly four times that the story was true. He was definite about this: “The fact that it is not invented fable but a genuine history is all-important,” he clearly wrote.

Plato’s ima ge of Atlantis as representing a Golden Age of mankind is so seductive and persuasive a thought that speculation about it has continued more or less uninterruptedly from the moment he first brought the subject up. Serious research began in the 17th century to try and ascertain the truth, or otherwise, of the existence of Atlantis. In 1882 and 1883 were published two masterpieces of research by the American Ignatius Donnelly: “Atlantis, the Antediluvian World,” and “Ragnarok, the Age of Fire & Gravel. Drawing on a huge number of deluge myths to support Plato’s account of how Atlantis disappeared in “violent earthquakes and floods in a single day and a night”, he believed that it had existed as a mid-Atlantic continent before 9,600 B.C. (Plato’s date), and was the first highly-advanced metal-working culture in the world.

ge of Atlantis as representing a Golden Age of mankind is so seductive and persuasive a thought that speculation about it has continued more or less uninterruptedly from the moment he first brought the subject up. Serious research began in the 17th century to try and ascertain the truth, or otherwise, of the existence of Atlantis. In 1882 and 1883 were published two masterpieces of research by the American Ignatius Donnelly: “Atlantis, the Antediluvian World,” and “Ragnarok, the Age of Fire & Gravel. Drawing on a huge number of deluge myths to support Plato’s account of how Atlantis disappeared in “violent earthquakes and floods in a single day and a night”, he believed that it had existed as a mid-Atlantic continent before 9,600 B.C. (Plato’s date), and was the first highly-advanced metal-working culture in the world.

Starting on the obvious assumption that Plato’s “beyond the Pillars of Hercules” can only mean: passing through the Straits of Gibraltar (on either side of which the pillars stood) and out into the Atlantic Ocean, Ignatius Donnelly compiled an impressive array of scientific evidence to seek a mid-Atlantic solution to Atlantis. Three of the arguments he put forward to prove that Atlantis really existed, and that it was located in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean are:

Plants and animals are common to both sides of the Atlantic; therefore, there must have been a land bridge between them.

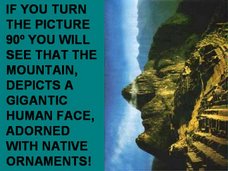

The many cross-Atlantic cultural similarities (e.g. pyramid building, mummification) must be derived from a central source. (Other researchers have, also, commented on the striking similarity between the pyramids of Egypt and those of Central and South America – pointing to the existence of a lost land-mass in the Atlantic which, with its central position, might have created links between America and the Old World).

Greeks, Egyptians, Celts and other Europeans all had legends of fairy-tale land masses in the Atlantic; the Aztecs of Mexico believed that they had migrated there from an island called ‘Aztlan’ – very close to the word Atlantis.

Another believer in the r eality of Atlantis was Otto Heinrich Muck, a Vienna-born engineer whose book: “The Secret of Atlantis,” was first published in Germany in 1976, 20 years after his death. Plato said Atlantis was located beyond the strait of Hercules which Muck, too, thought was the strait we call Gibraltar. This could place Atlantis in the vicinity of the Azores, a cluster of islands 1,200 kms. west of Europe. Since Plato wrote that the sea swallowed Atlantis, Muck decided to look for the lost island continent beneath the waves. Thanks to oceanography, we now have a comprehensive picture of the ocean’s floor: the Atlantic is divided into two parts by a 2,700 metre-high ridge that runs from Iceland in the north down to just short of the Antarctic shelf in the south. In the vicinity of the Azores, this ridge becomes a massive protuberance, almost 400 kms. wide, east to west, and 1,091 kms. long, with submarine volcanic mountains in the north. (Some of the peaks pierce out of the sea. These are the Azores). The size and shape of this undersea Azores plateau tallies to an amazing degree with Plato’s description of Atlantis.

eality of Atlantis was Otto Heinrich Muck, a Vienna-born engineer whose book: “The Secret of Atlantis,” was first published in Germany in 1976, 20 years after his death. Plato said Atlantis was located beyond the strait of Hercules which Muck, too, thought was the strait we call Gibraltar. This could place Atlantis in the vicinity of the Azores, a cluster of islands 1,200 kms. west of Europe. Since Plato wrote that the sea swallowed Atlantis, Muck decided to look for the lost island continent beneath the waves. Thanks to oceanography, we now have a comprehensive picture of the ocean’s floor: the Atlantic is divided into two parts by a 2,700 metre-high ridge that runs from Iceland in the north down to just short of the Antarctic shelf in the south. In the vicinity of the Azores, this ridge becomes a massive protuberance, almost 400 kms. wide, east to west, and 1,091 kms. long, with submarine volcanic mountains in the north. (Some of the peaks pierce out of the sea. These are the Azores). The size and shape of this undersea Azores plateau tallies to an amazing degree with Plato’s description of Atlantis.

What catastrophe destroyed Atlantis? Plato refers to a “deviation in their courses of the stars, and the destruction by fire of everything on earth.” M uck concludes that the deviant star was an asteroid, probably from the Adonis group, which circles the sun in dangerously eccentric orbits. This assumption is based on the evidence of undersea craters. Huge chunks of this asteroid, Muck believes, ripped through the earth’s crust at one of its sensitive points, the Atlantic Ridge, setting off every volcano in the chain. In the ensuing nightmare, during which the island continent was rocked by non-stop stupendous earthquakes of unimaginable magnitude, swamped by giant tidal waves and blanketed by oceans of red-hot lava, a rift was opened in the Atlantic bottom into which Atlantis sunk, leaving only the nine lava-covered cones of her tallest peaks to become the Azores – and a mysterious widening of the mid-Atlantic ridge.

uck concludes that the deviant star was an asteroid, probably from the Adonis group, which circles the sun in dangerously eccentric orbits. This assumption is based on the evidence of undersea craters. Huge chunks of this asteroid, Muck believes, ripped through the earth’s crust at one of its sensitive points, the Atlantic Ridge, setting off every volcano in the chain. In the ensuing nightmare, during which the island continent was rocked by non-stop stupendous earthquakes of unimaginable magnitude, swamped by giant tidal waves and blanketed by oceans of red-hot lava, a rift was opened in the Atlantic bottom into which Atlantis sunk, leaving only the nine lava-covered cones of her tallest peaks to become the Azores – and a mysterious widening of the mid-Atlantic ridge.

In the absence of archeological evidence, one might be tempted to dismiss Atlantis as a myth. But researchers like Donnelly and Muck have certainly advanced extremely persuasive arguments in favour of the reality of Plato’s lost continent Atlantis.

“Once upon a time,” according to the account given in Plato’s book, “there was, beyond the strait you call ‘The Pillars of Hercules’, an island larger than Asia Minor and Libya together…On this island of Atlantis, ther

e existed a great and admirable kingdom.” Plato proceeded to describe Atlantis further in another book: “Critias”, also written around 355 B.C. Atlantis was a semi-tropical island continent of, perhaps, 400,000 sq. kms, with an estimated population of 20 million. For centuries (12,000 to 9,000 B.C.), said Plato, the Atlanteans were the dominant civilization in their half of the world, ruling a Mediterranean empire that extended to the borders of Egypt and Italy. Eventually, wrote Plato, they became “obsessed with the wrongful pursuit of material gain and power”, and tried to conquer the entire Mediterranean world. They were beaten back by the ancestors of the Greeks.

e existed a great and admirable kingdom.” Plato proceeded to describe Atlantis further in another book: “Critias”, also written around 355 B.C. Atlantis was a semi-tropical island continent of, perhaps, 400,000 sq. kms, with an estimated population of 20 million. For centuries (12,000 to 9,000 B.C.), said Plato, the Atlanteans were the dominant civilization in their half of the world, ruling a Mediterranean empire that extended to the borders of Egypt and Italy. Eventually, wrote Plato, they became “obsessed with the wrongful pursuit of material gain and power”, and tried to conquer the entire Mediterranean world. They were beaten back by the ancestors of the Greeks.Then, according to Plato, “in a single dreadful day and a single dreadful night,” Atlantis was swallowed up by the sea.

Aristotle, Plato’s most famous disciple, believed that Plato had made Atlantis up, and this doubt has continued over the centuries. L. Sprague de Camp, in his scholarly work: “Lost Continents”, has analysed the

evidence carefully and convinced himself that “the most reasonable way to regard Plato’s story, then, is an impressive, if abortive, attempt at a political, historical and scientific romance – a pioneer science-fiction story”; his view is that, like Thomas More’s “Utopia”, Plato’s story described an ideal community as preconceived by the author.

evidence carefully and convinced himself that “the most reasonable way to regard Plato’s story, then, is an impressive, if abortive, attempt at a political, historical and scientific romance – a pioneer science-fiction story”; his view is that, like Thomas More’s “Utopia”, Plato’s story described an ideal community as preconceived by the author.However, more than 2,000 books on the subject disagree, and while it may be comfortable to take the orthodox line, the chances are that Atlantis actually existed.

For Plato goes out of his way to report exactly what were the origins of the Atlantis tale: Solon, a famous Greek elder statesman, had been given the story by the Egyptian priests of Sais, and had planned to write a poem on the subject. (Historically, there is no doubt that, after Solon’s retirement from public life, he travelled to the Mediterranean as a businessman, and there are a number of contemporary witnesses of his visit to Egypt around 600 B.C.) He told what he knew to an equally renowned Greek, Critias, whose grandson was the friend of Socrates who narrated the story in Plato’s books. These were all highly eminent people. Also, Plato affirmed flatly four times that the story was true. He was definite about this: “The fact that it is not invented fable but a genuine history is all-important,” he clearly wrote.

Plato’s ima

ge of Atlantis as representing a Golden Age of mankind is so seductive and persuasive a thought that speculation about it has continued more or less uninterruptedly from the moment he first brought the subject up. Serious research began in the 17th century to try and ascertain the truth, or otherwise, of the existence of Atlantis. In 1882 and 1883 were published two masterpieces of research by the American Ignatius Donnelly: “Atlantis, the Antediluvian World,” and “Ragnarok, the Age of Fire & Gravel. Drawing on a huge number of deluge myths to support Plato’s account of how Atlantis disappeared in “violent earthquakes and floods in a single day and a night”, he believed that it had existed as a mid-Atlantic continent before 9,600 B.C. (Plato’s date), and was the first highly-advanced metal-working culture in the world.

ge of Atlantis as representing a Golden Age of mankind is so seductive and persuasive a thought that speculation about it has continued more or less uninterruptedly from the moment he first brought the subject up. Serious research began in the 17th century to try and ascertain the truth, or otherwise, of the existence of Atlantis. In 1882 and 1883 were published two masterpieces of research by the American Ignatius Donnelly: “Atlantis, the Antediluvian World,” and “Ragnarok, the Age of Fire & Gravel. Drawing on a huge number of deluge myths to support Plato’s account of how Atlantis disappeared in “violent earthquakes and floods in a single day and a night”, he believed that it had existed as a mid-Atlantic continent before 9,600 B.C. (Plato’s date), and was the first highly-advanced metal-working culture in the world.Starting on the obvious assumption that Plato’s “beyond the Pillars of Hercules” can only mean: passing through the Straits of Gibraltar (on either side of which the pillars stood) and out into the Atlantic Ocean, Ignatius Donnelly compiled an impressive array of scientific evidence to seek a mid-Atlantic solution to Atlantis. Three of the arguments he put forward to prove that Atlantis really existed, and that it was located in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean are:

Plants and animals are common to both sides of the Atlantic; therefore, there must have been a land bridge between them.

The many cross-Atlantic cultural similarities (e.g. pyramid building, mummification) must be derived from a central source. (Other researchers have, also, commented on the striking similarity between the pyramids of Egypt and those of Central and South America – pointing to the existence of a lost land-mass in the Atlantic which, with its central position, might have created links between America and the Old World).

Greeks, Egyptians, Celts and other Europeans all had legends of fairy-tale land masses in the Atlantic; the Aztecs of Mexico believed that they had migrated there from an island called ‘Aztlan’ – very close to the word Atlantis.

Another believer in the r

eality of Atlantis was Otto Heinrich Muck, a Vienna-born engineer whose book: “The Secret of Atlantis,” was first published in Germany in 1976, 20 years after his death. Plato said Atlantis was located beyond the strait of Hercules which Muck, too, thought was the strait we call Gibraltar. This could place Atlantis in the vicinity of the Azores, a cluster of islands 1,200 kms. west of Europe. Since Plato wrote that the sea swallowed Atlantis, Muck decided to look for the lost island continent beneath the waves. Thanks to oceanography, we now have a comprehensive picture of the ocean’s floor: the Atlantic is divided into two parts by a 2,700 metre-high ridge that runs from Iceland in the north down to just short of the Antarctic shelf in the south. In the vicinity of the Azores, this ridge becomes a massive protuberance, almost 400 kms. wide, east to west, and 1,091 kms. long, with submarine volcanic mountains in the north. (Some of the peaks pierce out of the sea. These are the Azores). The size and shape of this undersea Azores plateau tallies to an amazing degree with Plato’s description of Atlantis.

eality of Atlantis was Otto Heinrich Muck, a Vienna-born engineer whose book: “The Secret of Atlantis,” was first published in Germany in 1976, 20 years after his death. Plato said Atlantis was located beyond the strait of Hercules which Muck, too, thought was the strait we call Gibraltar. This could place Atlantis in the vicinity of the Azores, a cluster of islands 1,200 kms. west of Europe. Since Plato wrote that the sea swallowed Atlantis, Muck decided to look for the lost island continent beneath the waves. Thanks to oceanography, we now have a comprehensive picture of the ocean’s floor: the Atlantic is divided into two parts by a 2,700 metre-high ridge that runs from Iceland in the north down to just short of the Antarctic shelf in the south. In the vicinity of the Azores, this ridge becomes a massive protuberance, almost 400 kms. wide, east to west, and 1,091 kms. long, with submarine volcanic mountains in the north. (Some of the peaks pierce out of the sea. These are the Azores). The size and shape of this undersea Azores plateau tallies to an amazing degree with Plato’s description of Atlantis.What catastrophe destroyed Atlantis? Plato refers to a “deviation in their courses of the stars, and the destruction by fire of everything on earth.” M

uck concludes that the deviant star was an asteroid, probably from the Adonis group, which circles the sun in dangerously eccentric orbits. This assumption is based on the evidence of undersea craters. Huge chunks of this asteroid, Muck believes, ripped through the earth’s crust at one of its sensitive points, the Atlantic Ridge, setting off every volcano in the chain. In the ensuing nightmare, during which the island continent was rocked by non-stop stupendous earthquakes of unimaginable magnitude, swamped by giant tidal waves and blanketed by oceans of red-hot lava, a rift was opened in the Atlantic bottom into which Atlantis sunk, leaving only the nine lava-covered cones of her tallest peaks to become the Azores – and a mysterious widening of the mid-Atlantic ridge.

uck concludes that the deviant star was an asteroid, probably from the Adonis group, which circles the sun in dangerously eccentric orbits. This assumption is based on the evidence of undersea craters. Huge chunks of this asteroid, Muck believes, ripped through the earth’s crust at one of its sensitive points, the Atlantic Ridge, setting off every volcano in the chain. In the ensuing nightmare, during which the island continent was rocked by non-stop stupendous earthquakes of unimaginable magnitude, swamped by giant tidal waves and blanketed by oceans of red-hot lava, a rift was opened in the Atlantic bottom into which Atlantis sunk, leaving only the nine lava-covered cones of her tallest peaks to become the Azores – and a mysterious widening of the mid-Atlantic ridge.In the absence of archeological evidence, one might be tempted to dismiss Atlantis as a myth. But researchers like Donnelly and Muck have certainly advanced extremely persuasive arguments in favour of the reality of Plato’s lost continent Atlantis.